Oak performance II: Benchmarking Oak's HTTP server

So far, when I've tried to measure Oak's performance, I've used CPU-intensive tasks that are bounded by CPU and memory performance of the underlying hardware. But another useful dimension of performance to measure, especially for a language like Oak that I often use to build web services, is how efficient its web server can be.

The measurements

When we measure a web server's performance, there are a few different metrics we can pay attention to. The most common ones are:

- Throughput: How many requests can the server respond to in a given duration of time? A simplistic way to think about this is "hits per second" that the server can sustain. In this post, we'll measure throughput as requests completed every second.

- Latency: How quickly does the server respond to each request? We can understand this roughly as how long the client or web browser spends waiting for a response on an average request, when the server is fully loaded. Latency should be measured as a distribution, rather than a single number or average, because it tends to have a long "tail" that disproportionately impacts real-world experience. In this post, we'll measure latency by reporting on the average, as well as the minimum/maximum range.

- Memory usage: Self-explanatory. How much memory does the server need to sustain some throughput and latency? I eyeballed this using my Mac's system monitor app, because it tends to stay roughly constant and I didn't really need an exact measurement.

Some people also often measure the number of concurrent connections the server can sustain, and how that affects memory usage, but that wasn't a focus of my investigation this time, because it requires a slightly different experimental setup that I didn't have time to build -- we'll take a quick look at concurrent connection counts towards the end of the post.

To make these measurements, I set up a server program, whose only job will be to accept and respond to HTTP requests as quickly as possible, and a hammer program, which will try to send as many HTTP requests as possible to the server program, sequentially.

The hammer program is straightforward: it sends as many requests as the server will respond to, sequentially, in a loop every second, and reports the throughput and latency for that second.

std := import('std')

math := import('math')

fmt := import('fmt')

fn hammer {

latencies := []

start := nanotime()

reqs := with std.loop() fn(reqs, break) {

a := nanotime()

req({ url: 'http://127.0.0.1:9090/' })

latencies << nanotime() - a

if nanotime() - start >= 1000000000 -> break(reqs)

}

fmt.printf('{{ 0 }}req/s\tlatency = {{ 1 }}µs ({{ 2 }}-{{ 3 }}µs)'

reqs

math.round(math.mean(latencies) / 1000, 3)

math.round(math.min(latencies...) / 1000, 3)

math.round(math.max(latencies...) / 1000, 3)

)

}

with std.loop() fn {

hammer()

}The script outputs a line every second that looks like this:

3924req/s latency = 247.317µs (163-1257µs)Here, the benchmarked server handled about 4,000 requests every second, with an average latency of 247µs, but latencies as low as 163µs and as high as 1.3ms were observed. You can take a look at the full output I gathered for every benchmark in the raw output text file.

The subjects

Most Oak web services use the http module in Oak's standard library to set up web servers. The http module provides a convenient way to set up and handle parameterized routes, but it also comes with a slight performance overhead incurred by that convenience. Real-world apps, of course, will have further overhead above that of the http module that comes from the business logic in the apps themselves. To account for these different costs, I wrote a few different variants of web servers to benchmark:

Basic: This is the most minimal, fastest web server possible in Oak. It parses an incoming HTTP request and responds with a single byte of data, but otherwise doesn't do any further processing. It should give us a sense of what the overhead of Oak's interpreter is when running a web server -- overhead that comes mostly from the internals of the Oak runtime and Go's HTTP parser.

with listen('0.0.0.0:9090') fn(evt) if evt.type {

:error -> std.println('Could not start server.')

_ -> evt.end({

status: 200

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' }

body: '.'

})

}HTTP: This is a web server that demonstrates an "idiomatic", if simple, usage of the http module in Oak's standard library. This benchmark will hopefully show us the overhead of the http library itself, which does some work to parse HTTP routes and decode query strings, match the request with the right handler, and set some custom headers.

http := import('http')

server := http.Server()

with server.route('/') fn(_) fn(req, end) if req.method {

'GET' -> end({

status: 200

headers: { 'Content-Type': http.MimeTypes.txt }

body: '.'

})

_ -> end(http.MethodNotAllowed)

}

std.println('mode: http')

server.start(9090)App: This benchmark used the current revision 0792440 of the Oak application that serves this website, oaklang.org. It should demonstrate how a real-world web app built with Oak and its http module performs, as it handles many different routes, larger responses, and more logic in the request-response path.

In addition, I also benchmarked two "control" scenarios with the same setup, to provide some reference metrics for comparison later:

No server: This benchmark ran the hammer script against a closed TCP port, meaning every request failed with a connection error. It gives us a sense of how quickly the operating system can handle incoming connection requests, and any overhead the testing script itself incurs.

Node.js: This is a very minimal Node.js web server using an HTTP server from Node's http standard library module, which parses HTTP requests and responses but otherwise doesn't perform much logic. Like the "Basic" Oak web server, this Node.js server responds with a single byte \x2e to every request. Node.js's web server is a battle-tested, production-grade HTTP server, so this control should be a good reference point to get a feel for how "slow" Oak's relative performance is.

const http = require('http');

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' });

res.end('.');

});

server.listen(9090);To make all of the measurements we'll see, I started the web server, and started three hammer processes running in parallel. Each new hammer process was effectively a new "concurrent" connection, and I observed empirically that beyond three concurrent hammer processes, total throughput stayed about the same. (More on high-concurrency cases later.) When looking at all of these outputs from the hammer script, we should keep in mind that there are three of these hammer processes running, so the true throughput is 3x what's reported by each script. The graphs and numbers I show below account for that multiplier.

Lastly, all of these tests were done on a 2013 15" MacBook Pro with an Intel Core i7-4850HQ (I know, it's old) running from AC power. If you have a recent laptop, you'll probably see better results, but the comparisons shouldn't be very different.

The results

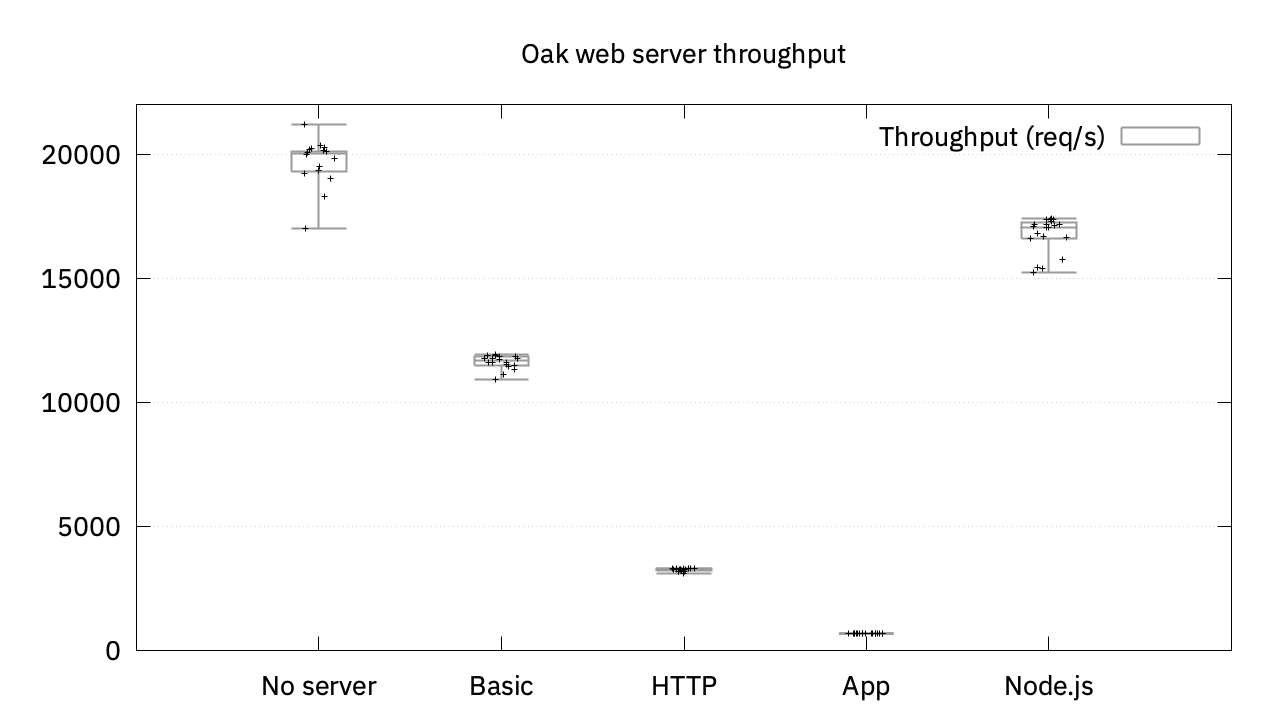

We can take in the high-level conclusions from the benchmark in two charts, which I'll share here. I've also made the full data for all of these benchmarks available in this text file if you want to take a closer look yourself.

First, let's look at the throughput measurements.

With this particular benchmark setup, around 20kreq/s is our baseline. Node.js comes pretty close, with around 17kreq/s, and Basic, HTTP, and App servers score lower by comparison, in that order. My main takeaways here were:

- Oak doesn't blow me away, but it's not very slow either, in its fastest setup that's comparable to the Node.js server. It scores within the ballpark of Node.js, a production-grade HTTP server.

- The performance gaps between the three Oak servers correspond very directly to the amount of logic performed by the corresponding programs, which suggests to me that speeding HTTP and App benchmarks up will likely involve optimizing the Oak interpreter loop itself, rather than the HTTP request-handling code.

As an interesting point of comparison, though Node.js doesn't officially report any benchmarks, Deno, a TypeScript runtime built on the V8 JavaScript engine, has an official page where the team reports on continuously run benchmark results, including some benchmarks on Deno's HTTP web servers.

Deno's equivalent benchmark to our Node.js and Oak "Basic" benchmarks, which they label "deno_http" and "node_http", hover around 30,000-40,000req/sec, which seems plausible compared to our measurement of around 17,000req/s on our Node.js server -- faster, newer hardware can probably account for the discrepancy of around a 2x gap in performance.

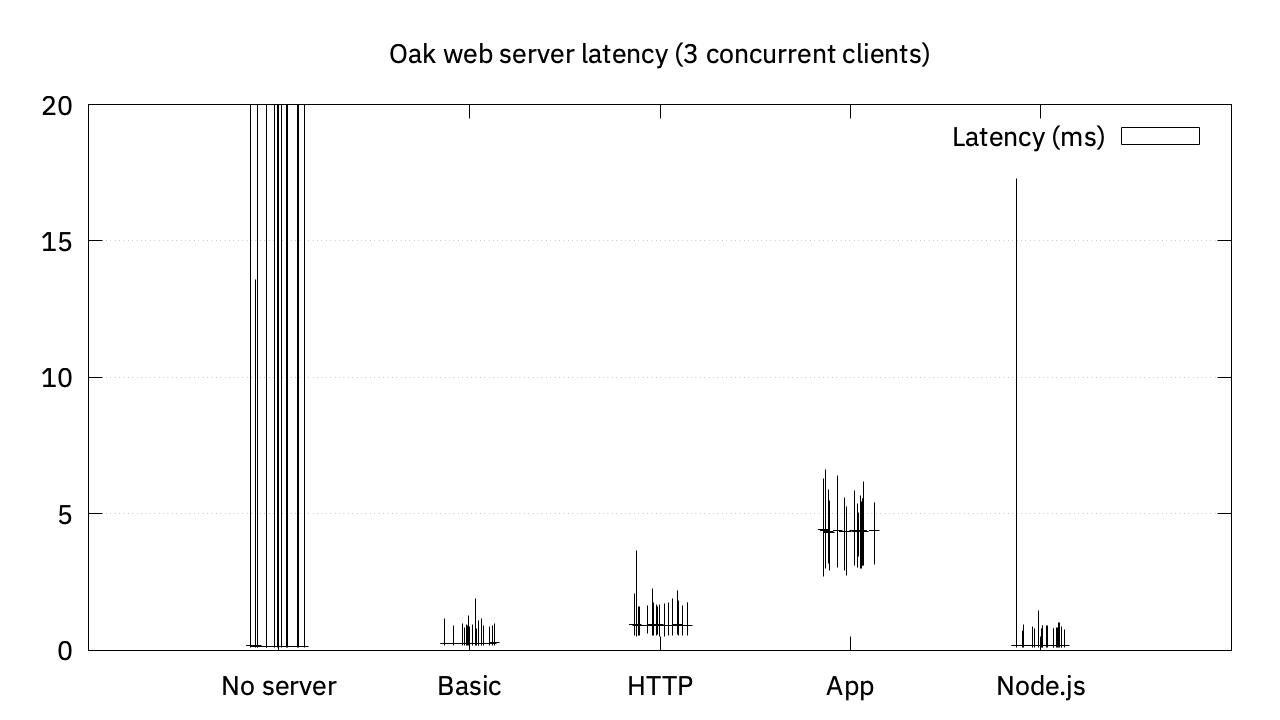

Here's a similar look at the latency measurements.

I'm not sure how to take the "No server" metrics, especially because the tail latency spikes to above 50ms (and overflows this chart). Perhaps the operating system shows very high variance in the time it takes to drop connection requests to closed ports? Maybe the OS's networking stack does some request coalescing? I'm not really sure. But I chose to move on past that rabbit hole. (If you have educated guesses, I'm curious to hear about them.)

The rest of the latency measurements, again, make a lot of sense. Both Node.js and the Basic Oak server perform comparably, at sub-millisecond latencies. For more complex Oak servers, the latency moves up to 3-5ms as the programs themselves involve more logic. In a moment, I'll have more to say on how latency moves up with many more concurrent connections.

I wasn't particularly concerned about memory usage in either of these benchmarks, because both Oak and Node.js use very efficient asynchronous programming primitives -- Go's goroutines in Oak, and the libuv event loop in Node.js. Nonetheless, I did glance at my Mac's system monitor during these benchmarks, and noticed that Oak hovers around 8-10MB and Node.js hovers around 35-40MB memory usage during the benchmark runs. These measurements stay about the same, even as the number of concurrent connections go up beyond 3 and up to 100, which suggests, I guess, that the very efficient concurrency primitives are indeed very efficient!

A note about connection reuse, concurrency, and latency

In all the tests I've shared so far, we've observed latencies in the <1ms range, which is quite good! But this is mostly because our tests don't hit the servers with many concurrent requests. Latency and memory usage both tend to go up as the number of concurrent connections go up, and we've only had a maximum of 3 concurrent requests in flight so far. With the hammer script I had written, it wasn't very easy to see how the servers performed in highly concurrent scenarios.

My existing tests also had another potential blind spot, which is that it doesn't take advantage of HTTP keep-alive to reuse the same connection for consecutive HTTP requests, but creates a new TCP connection for each request. This limitation exists because Oak's built-in req() function for HTTP requests doesn't allow the underlying TCP connection to be reused. But the consequence of this limitation is that for fast web servers like the Node.js server, we may be testing not only how well the HTTP server performs, but also how quickly the underlying TCP server can accept and negotiate connections. In other words, the tests above using the hammer script may be under-estimating the performance of servers that can perform better with HTTP keep-alive.

To investigate both of these possibilities, I chose to corroborate my initial benchmark results with a third-party tool for benchmarking HTTP servers called Autocannon. Autocannon benchmarks can take advantage of HTTP keep-alive, and it allowed me to specify exactly how many concurrent clients I wanted to use in my benchmarks with a simple command line flag, solving both of our potential issues.

I ran Autocannon against 4 of the 5 scenarios above (all of them except the "No server" dummy case) with 100 concurrent clients for 30 seconds each:

npx autocannon -c 100 -d 30 http://localhost:9090To my pleasant surprise, most of my findings from the hammer script benchmarks matched up well with what Autocannon reported. There were two new results that are worth noting.

First, there was a visible uptick in request latency with 100 concurrent connections. (Showing Average ± Std. dev., 99%'ile, and maximum measurements.)

- Basic: 5.66ms ± 1.05ms ... 99% 8ms ... max 39ms.

- HTTP: 32.32ms ± 0.83ms ... 99% 35ms ... max 47ms.

- App: 149.13ms ± 5.31ms ... 99% 160ms ... max 239ms.

- Node.js: 3.12ms ± 1.21ms ... 99% 6ms ... max 38ms.

The bare-bones Oak HTTP server compares decently to the Node.js server, both around 3-5ms. As the amount of computational work required per request goes up, HTTP and App servers both show higher latency. This suggests that the bottleneck here is probably the performance of the Oak interpreter itself, rather than something specifically within the HTTP request-response path in the Oak runtime or HTTP parser/serializers. Though I'm not amazed by the results, if one of my Oak-based web apps were getting thousands of requests every second with 150ms latency, I think I wouldn't be too worried.

The second interesting finding from the Autocannon benchmarks was that, with HTTP keep-alive (and probably other small things Autocannon does that I'm unaware of), the Node.js server handled 27,000req/s, far higher than the 17,000req/s that earlier benchmarks from the hammer script reported. Other benchmarks on the Oak-based web servers, however, returned roughly consistent results within a few percent of their initial measurements. My best educated guess for what accounts for the gap is the overhead of re-establishing TCP connections that underlie the HTTP requests, because the Oak benchmarks didn't take advantage of keep-alive.

My takeaways

In the course of developing Oak, I've made lots of performance measurements, but all of my previous benchmarks that I can recall measured CPU performance or memory utilization, which are both straightforward to measure and understand -- if something took twice as long, it's twice as slow! Benchmarking I/O was a new and interesting experience. I learned about how to (and how not to) measure latency, HTTP keep-alive, concurrency, and even how to use gnuplot, which I used to draw the charts in this post.

My main takeaway at the end of this process is that Oak is more than fast enough for my use cases, and further performance improvements will probably involve speeding up the interpreter loop itself. Oak's baseline performance, from the "Basic" benchmark, matches up well against production-grade servers like Node.js, because the Basic benchmark is mostly concerned with performance of the underlying TCP and HTTP connection-handling logic, which in Oak is written in Go with Go's excellent net/http standard library package. The benchmarks showed that Oak's throughput and latency degrades predictably as the server's response logic gets more and more complex, which signals that the bottleneck is probably not with the Oak runtime's HTTP request handling code, but with the speed of Oak's interpreter loop instead, and how quickly Oak can execute Oak code.

It was also very interesting to see the scaling behaviors of Oak's web server up close and in person, both as the number of requests-per-second increased, and as I added more connections to the server. It was satisfying to see the memory usage stay so stable, and educational to see exactly how latency suffered as the number of concurrent connections to servers increased to 100 and beyond.

Obviously, Oak will continue to improve in many ways, but I think what I saw here is a solid foundation, especially for my personal use cases of building personal tools and projects. For my projects and websites running on Oak, I can be pretty confident that the next Hacker News or Reddit Front Page stampede won't bring my servers to their knees.